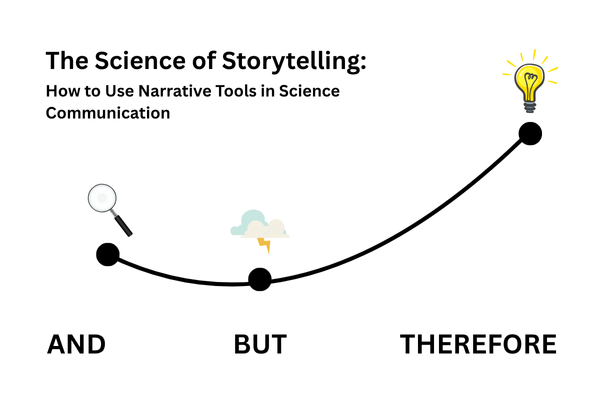

Tell someone a story, and their brain lights up in sync with yours. That’s what neuroscience shows—and why nothing in science communication makes sense except in light of narrative. Stories make science human and memorable. But weaving data into a compelling story is hard. Therefore, frameworks like ABT—the And, But, Therefore model—can help scientists bring structure and meaning to their message.

This piece is the first in a three-part series inspired by Randy Olson’s Houston, We Have a Narrative. It explores why storytelling works, which tools make it powerful, and how to use them right now.

Why Narrative Works: The Neuroscience of Storytelling

Stories are the brain’s native language. At Princeton University, neuroscientist Uri Hasson showed that when people watched a narrative film, their brain activity synchronized with the story. This “neurocinematics” effect demonstrated something profound: narrative unifies the thinking of a group.

For effective communication, you need to pull everyone together. And that is what a clear problem does.

Facts activate isolated brain regions, but stories engage the full network—language, sensory, and emotional centers—making information easier to remember and relate to.

That’s why phrasing matters. Here’s what information without structure sounds like:

“Viruses are airborne pathogens. Our nasal system produces mucus to help trap and discard them. Cold air dries out that mucus, and viruses make it through.”

Compare to this short passage from my Curiosity Hut article:

“Because viruses are microscopic, they linger in the air after someone coughs or sneezes. That’s where our nose comes in—it’s our first line of defense. It produces mucus that traps and neutralizes invaders. Tiny hairs push the gunk down our throat, where we either swallow or spit it out. But cold air dries out mucus, weakening our defense. More viruses slip through, overwhelming our immune system. That’s why flu season coincides with chilly months.”

Same science, different impact. What makes the second version memorable isn’t just tone—it’s structure. The passage follows a cause → conflict → resolution arc: the essence of storytelling. In other words, it follows the ABT.

The ABT Framework: From Data to Drama

The And–But–Therefore model, developed by Randy Olson, gives communicators a simple way to create narrative flow:

- And sets up the context or agreement.

- But introduces conflict or contrast.

- Therefore delivers resolution or consequence.

It mirrors the classic three-act story, and it works at every scale—a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire paper.

Sentence example: “Our oceans are warming, and coral reefs are vital to marine life, but rising temperatures are killing them; therefore, scientists are racing to predict bleaching events.”

Paragraph example: My flu-season passage shows how ABT operates. It builds a context (“our nose protects us”), introduces a problem (“cold air weakens that defense”), and resolves it (“that’s why flu season coincides with winter”). The opening paragraph of this article is another great example.

Even Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address follows this rhythm: a nation founded on equality (and) is tested by war (but) and must be reborn in freedom (therefore).

The ABT isn’t a gimmick—it’s a skeleton that gives your message motion and direction.

Avoiding the “And, And, And” Trap

Without contrast, a story flattens into a list of events. Many science communicators fall into what Olson calls the AAA problem—a flat chain of “and, and, and.” Example:

“Last year, our neighborhood in Chicago experienced several floods. Basements filled with water, and residents waited for the city to take action. Eventually, community members organized to install small patches of green infrastructure—like rain gardens and permeable pavement—to manage the excess water. The measures worked, and the flooding problem was reduced.”

There’s no tension, no reason to care. The fix? Find the “but.”

“Chicago neighborhoods are having flooding issues, but local activists have found GI solutions, so they started a committee to build them” (Full story)

The moment you add a “but,” the story wakes up. ABT helps you cut clutter, find direction, and make meaning from complexity.

Finding Your Theme: The Dobzhansky Template

To find your story’s aboutness, Olson borrows from geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky, who wrote:

“Nothing in biology makes sense except in light of evolution.”

He calls it the Dobzhansky Template:

“Nothing in ___ makes sense except in light of ___.”

It’s a powerful way to identify your theme—the unifying principle that guides every sentence. Examples:

- “Nothing in climate adaptation makes sense except in light of resilience.”

- “Nothing in artificial intelligence makes sense except in light of human judgment.”

Once you have that, your ABT practically writes itself.

In Olson’s workshops, he asked participants to describe a painting. Without a narrative framework, their explanations took 30 seconds and rambled. They were just listing the things they saw. When told to use an ABT, they delivered a crisp, 13-second story that conveyed both meaning and feeling. “There are three people in a room AND the sunlight from the window indicates late afternoon, BUT the woman in the middle appears to be questioning the man sitting down, THEREFORE the painting looks like an interrogation.”

Narrative gives focus and momentum—it helps the brain decide what to keep and what to skip.

The Narrative Spine: Keeping the Story on Track

The narrative spine is the backbone of your piece: a clear line of change that connects beginning, middle, and end. In science writing, it often looks like this: A mystery is observed → a scientist investigates → something new changes what we know.

If ABT gives you the vertebrae, the narrative spine connects them into a living structure. Before you start writing, try summarizing your story in a single ABT sentence. If you can’t, you haven’t yet found your focus.

Therefore: Tell Better Stories

Science reveals how the world works, but without narrative, its discoveries can fade into noise. Therefore, science communicators must learn to tell stories that move both the heart and the mind.

The ABT framework, the Dobzhansky template, and the idea of a narrative spine are tools anyone can use to bring structure and emotion to complex ideas. They don’t simplify science—they clarify it.

As Hasson’s research shows, a good story doesn’t just inform—it synchronizes minds. It brings people together, aligning understanding and emotion. A good story unifies people from all backgrounds around a shared “but”—a common challenge that drives curiosity and connection. That’s the science of storytelling.

Leave a Reply