In my ten years at the bench prior to joining The Kavli Foundation’s Science and Society team, I frequently found myself drawn toward opportunities to share my science, as I expect many of you are as well. As someone who, more often than not, was working on basic science projects, I struggled to find the best way to do this. I was encouraged to make my work ‘relevant.’ But it felt like all anyone ever wanted to hear about was the far off, downstream applications (someday, someone else three projects in the future MIGHT use this to make a cancer drug… maybe), which both felt disingenuous and undercut the value of my work trying to understand the world around us. So, what’s a basic scientist to do?

Enter: SciPEP. The Science Public Engagement Partnership was a joint effort by The Kavli Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. This effort was led by Brooke Smith (Kavli), Rick Borchelt (DOE), and Keegan Sawyer (DOE), with support from many other Kavli and DOE staff, myself included. Over the last four years, SciPEP has worked to deepen our understanding of effective public engagement around basic research. This included commissioning landscape studies (similar to a review article that also analyzes what it finds), hosting conferences, and sharing our learnings from across the field – all of which are available in full on our resources page.

If you’re short on time but still intrigued, I’d especially recommend you take a look at the Insights report (available as a traditional PDF or as a beautiful digital-magazine). This report is the culmination of all of the SciPEP efforts all rolled into one easy-to read package. It is a synthesis of five years’ worth of work that summarizes themes, takeaways, tips, and new questions to explore for basic scientists, science communicators, communications trainers, social science researchers, and more. As a side note, all of this work was created with basic science in mind, but like all good advice it has broad applicability – so regardless of if your science leans more basic, more applied, or a mix of both, I suspect there is something here (both this blog post and the Insights report) for you. As someone who has done basic science and as a member of the Kavli-DOE team that helped SciPEP insights emerge, below are a few elements that resonated strongly for me. I hope they might for you as well.

Strategic Science Communication

To be totally honest, while I was at the bench trying to navigate engagement opportunities, I’m not sure I had ever heard of strategic science communication. In short, it means there is increased return on your engagement investment when you take the time to identify communication goals and work to understand your audience before diving into any science engagement/communication—which it turns out can be a LOT harder than it sounds, especially for basic science. What strategic science communication even looks like for basic science is an active area of research (here, here, and here for a specific examples).

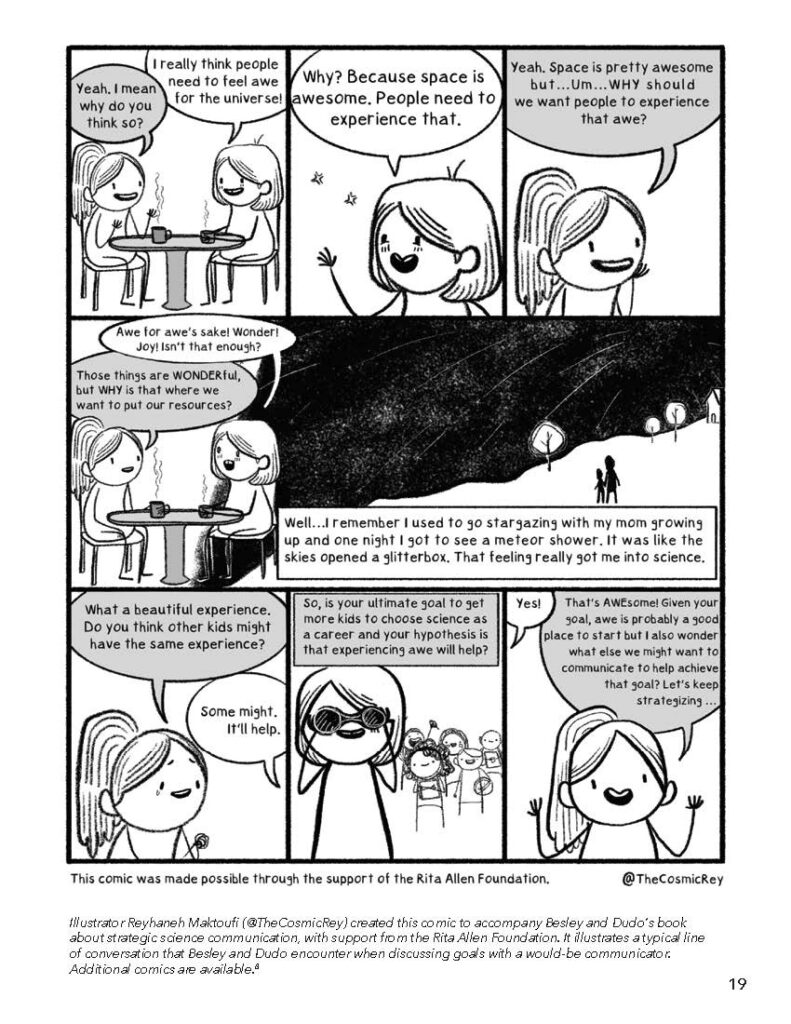

So, we want to set goals and understand our audience in order to communicate strategically – but how does that actually work for basic science? A recent study by researchers John Besley and Anthony Dudo explored basic scientists’ views about different engagement goals for their science communication and found that basic scientists tended to prioritize every goal highly (full report here). This may seem great on the surface, but if we are prioritizing everything highly, it makes me wonder if we are actually prioritizing anything at all. Strategic science communication can be a big ask, requiring communicators to take time for deep introspective reflection, but setting clear goals will improve the impact of your scicomm.

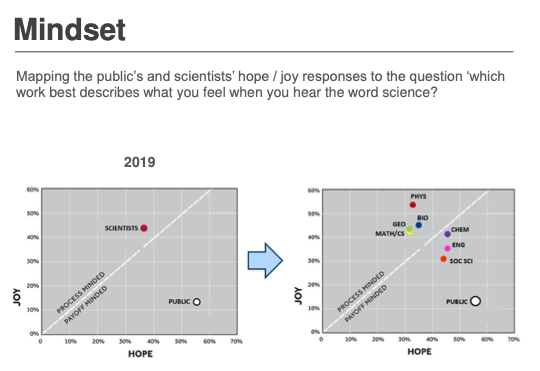

On the audience’s side of things, there are many studies that have explored how their views of science differ from those of scientists (selected studies are summarized in this report by ScienceCounts). One that stood out starkly to me was the difference in responses when asked “Which word best describes what you feel when you hear the word science?” Most members of the public responded with something along the lines of ‘hope’ while many scientists, particularly those in more ‘basic’ science fields, responded with feelings closer to ‘joy’ (of note, hope is also a common response among scientists). This difference can be important to keep in mind when creating and doing engagement and communications.

Curiosity

Curiosity can be a huge boon for getting audiences to the door, especially for basic science engagement, but it may not always be enough to help them walk through it. Scientists often rely on sharing why our work is ‘cool’ (to us) but sometimes we need to take the next step and figure out why it is ‘cool’ to our audience. Researcher Daniel Silva Luna shares the wisdom that your awe may differ from someone else’s, centering the core tenet of ‘know your audience.’ Fortunately, from psychologist Tania Lombrozo’s work we learned that curiosity is contagious and can be its own positive feedback loop.

Making your Science Relevant

“Make it relevant…” If I had a nickel for every time I was told that about my basic science, well, I’d probably have around $20, but you get the point. And every time I heard it, I bristled. It felt like finding the ‘relevance’ took away from the basic science—I was defaulting to finding an application, which made me feel like I was selling my science short. In the Insights resource (and in the 2023 SciPEP conference), Mónica Feliú Mójer shares a different perspective on relevance: focusing on connection rather than solely application. Mónica encourages researchers to think more broadly, emphasizing that “While utility implies a direct practical benefit, relevance transcends applications, encompassing a broader connection to people’s lives, cultures, and identities.”

In her article, Mónica puts into words something I had been feeling and grappling with unconsciously for most of my scientific career. She shares several examples, including the story of Corey Gray, a physicist at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and a member of the team who first observed gravitational waves. In her article she recounts, “The announcement of this breakthrough was an opportunity for Gray to connect his science to his identities, culture, and community. Gray and Sharon Yellowfly, his mother, are members of the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. Yellowfly is one of a handful of people who have helped preserve their indigenous language. Mother and son collaborated to translate the news into their endangered language. The act was more than mere translation. In many ways, it was Gray taking his science home.”

By communicating about gravitational waves in the Blackfoot language, Gray and Yellowfly made science more accessible, understandable, and thus, more relevant to the lives of Blackfoot people.

By thinking about connection, and not just utility, we can make communicating basic science stronger all around.

As SciPEP has come to a close, I am so grateful for the opportunity to be a part of this work at The Kavli Foundation – to help create the resources and scholarship I was searching for during my time at the bench. This all comes at an opportune time as many in the scientific community are looking for ways to meaningfully connect with people in their communities or outside their labs. If this leaves you with more questions than answers (and I hope for many of you it does!) I’d encourage you to do some of your own digging and research (and the SciPEP resources are a great place to start)—I can’t wait to see what’s next for this field!

Leave a Reply